Vegan Nasi Goreng

Ingredients

1.5 cups (250g) jasmine rice

1 onion, diced

5 cloves garlic, minced

3/4 cup mushrooms, chopped

1 spring onion, chopped

2 chili peppers, chopped

3 tbsp ketjap manis

1 tbsp soy sauce

2 tsp ginger

2 tsp cumin

2 tsp coriander

1 tsp turmeric

Salt

Pepper

For the garnish:

1 cucumber, chopped

Pickles

Sambal

Instructions

- Prepare the rice in a rice cooker. Set aside.

- Saute onions and garlic over medium heat until translucent (~5 minutes).

- Add the mushrooms and chili peppers and cook until soft (~5 minutes).

- Add all spices and sauces, mixing to coat. Add the cooked rice, stirring until everything is combined. Cook for another five minutes, then serve with sambal, pickles, and cucumbers

A longer and more detailed description

So I know it looks like this is just fried rice, and that would be because it is. But it’s tasty fried rice, and it was my favourite food as a kid, so this is what we’re making.

Start by making rice, then ignoring it. The further in advance you make the rice, the better, as old rice is the rice that’s meant for fried rice. Once you have your rice, though, either cooking or in a box, looking at you expectantly, make your vegetables. Add your usual suspects of onions and garlic, then add mushrooms and chili peppers, and then add your pile of spices and sauces, making sure everything is all nice and coated. Add your rice, stir some more, et voila. Nasi goreng. Selamat makan!

Suggestions and substitutions

For the ketjap manis - Ketjap manis is a sweet soy sauce, a bit thicker than tamari and with a rich flavour. While I do recommend finding it if you can since it’s just a generally lovely sauce, you can also substitute with soy sauce mixed with sugar or molasses.

For the sambal - Sriracha is a valid substitute.

For the chili peppers - Hey, my lombok is finally an appropriate pepper! :D

For the vegetables - Each region of Indonesia has its own variations on what vegetables they add into nasi goreng. I wanted to keep this fairly simple and accessible, so I went with mushrooms and spring onions. However, if there’s something else that calls to you, by all means, add it. This is a very flexible dish.

For the cucumbers - I strongly prefer eating this with pickles sliced in, and my partner very much does not. Cucumbers are a compromise.

What I changed to make it vegan

There are many, many variations of nasi goreng, many of which include fish or shrimp. It’s also very common to top nasi goreng with a fried egg. I didn’t do any of this, but instead went for a nasi goreng that’s more like what I ate as a kid. It’s probably less accurate to true Indonesian nasi goreng, but it is vegan, and it is delicious.

What to listen to while you make this

May I introduce you to possibly the weirdest music I’ve found in this series, Arrington de Dionyso’s Maliakat dan Singa? Whatever you think it is from that name, I promise you, it’s not.

A bit more context for this dish

It is unsurprisingly difficult to summarise the cuisine of a country the size and diversity of a small continent. Indonesia is spread across over 17500 islands and 600 ethnic groups, many of which have their own languages, cultures, and traditions. Geographically, it’s home to one of the starkest visible biological divides, multiple tectonic plates, and 17% of the world’s wildlife. It is home to 10% of the world’s languages, 3% of the world’s population, and is the source of some of the foods now considered staple to the vegan diet, like tempeh and a massive variety of spices. Traders from Indonesia’s islands have been traversing the Indian Ocean basin for millennia, making Indonesia a fundamental part of the world’s culinary traditions.

All this to say that describing Indonesia’s cuisine in a paragraph is an exercise in futility. Instead, I think it’s interesting to consider why nasi goreng has become a de facto symbol of the country, and indeed, of the region more generally.

Indonesia is a massively diverse place. (Source: Wikipedia)

Indonesia is a massively diverse place. (Source: Wikipedia)

While rice has occupied a central space in Indonesian (or at least Sulawesi) cuisine since at least 3000BCE, nasi goreng itself has not. The concept of fried rice, while not new per se, is less old than you might think. Fried rice first appeared in China during the Sui Dynasty in the 6th century CE as a solution for what to do with leftover rice. Easy to make and easy to fill with whatever was lying around, the dish grew in popularity, eventually travelling with Chinese sailors as they journeyed throughout the Pacific. When the Chinese chuan began appearing off the coasts of Indonesia’s islands in the 10th century, they had fried rice on board.

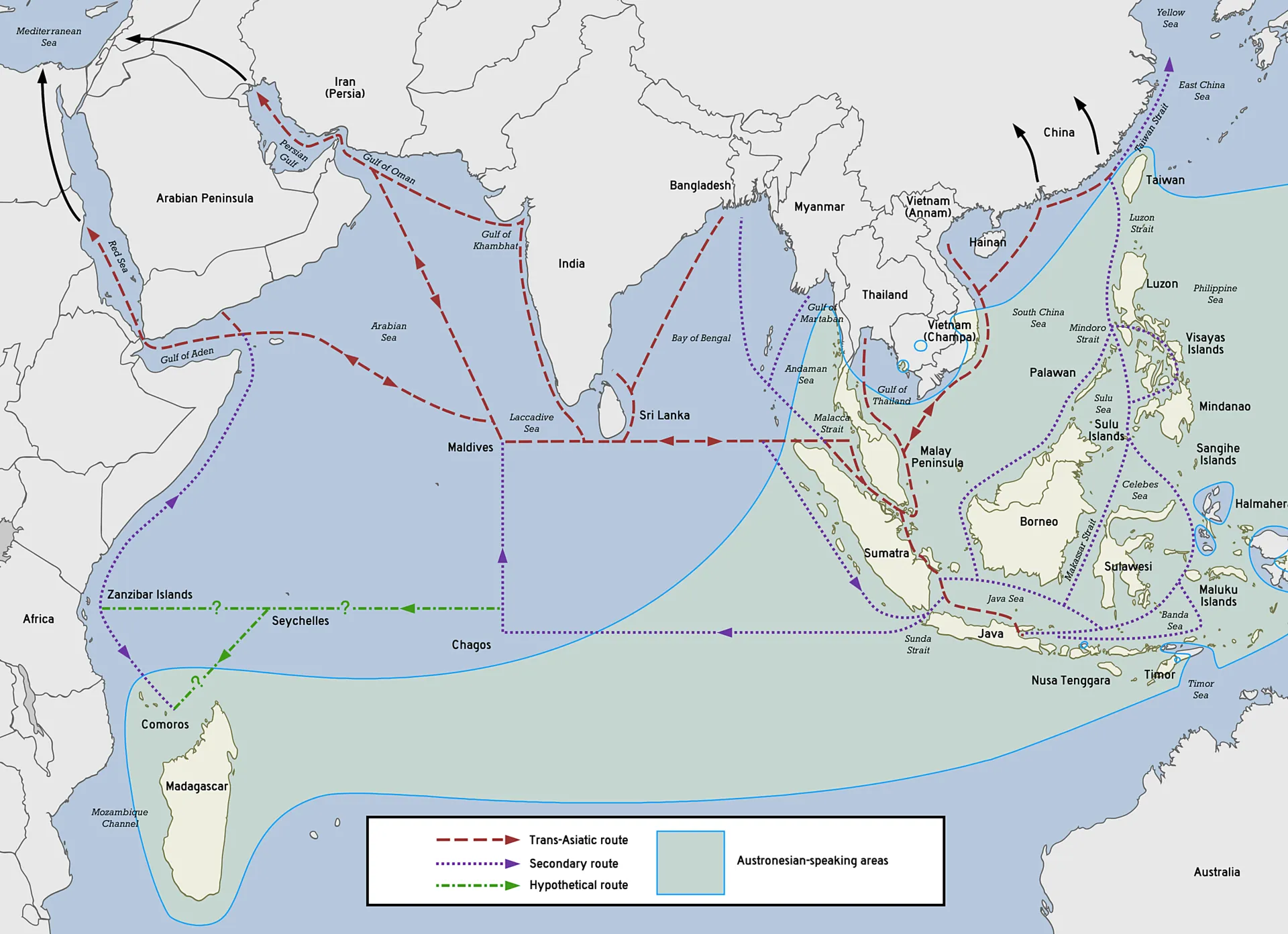

I like that I will always find a way to incorporate a map, and there's nothing you can do to stop me. (Source: Wikipedia)

I like that I will always find a way to incorporate a map, and there's nothing you can do to stop me. (Source: Wikipedia)

Fried rice is a very convenient food. Beyond being able to be made with basically anything, it’s also a food that lends itself well to any meal and to whatever circumstances it finds itself in. As Chinese sailors and traders - and later immigrants - arrived in Indonesia, their soy sauces and fried rice adapted to the local Indonesian ingredients, with soy sauce being modified with palm sugar to become ketjap manis, and the fried rice incorporating the bountiful fish that served as a basis of many of the islands’ cuisines.

These were, of course, not the only dishes Chinese traders and immigrants brought with them. Indonesian cuisine has been heavily influenced and shaped by centuries of trade across the Pacific. However, it does illustrate how malleable cuisine is and how much trade shapes what we eat.

This became especially true with the arrival of the Dutch to Indonesia.

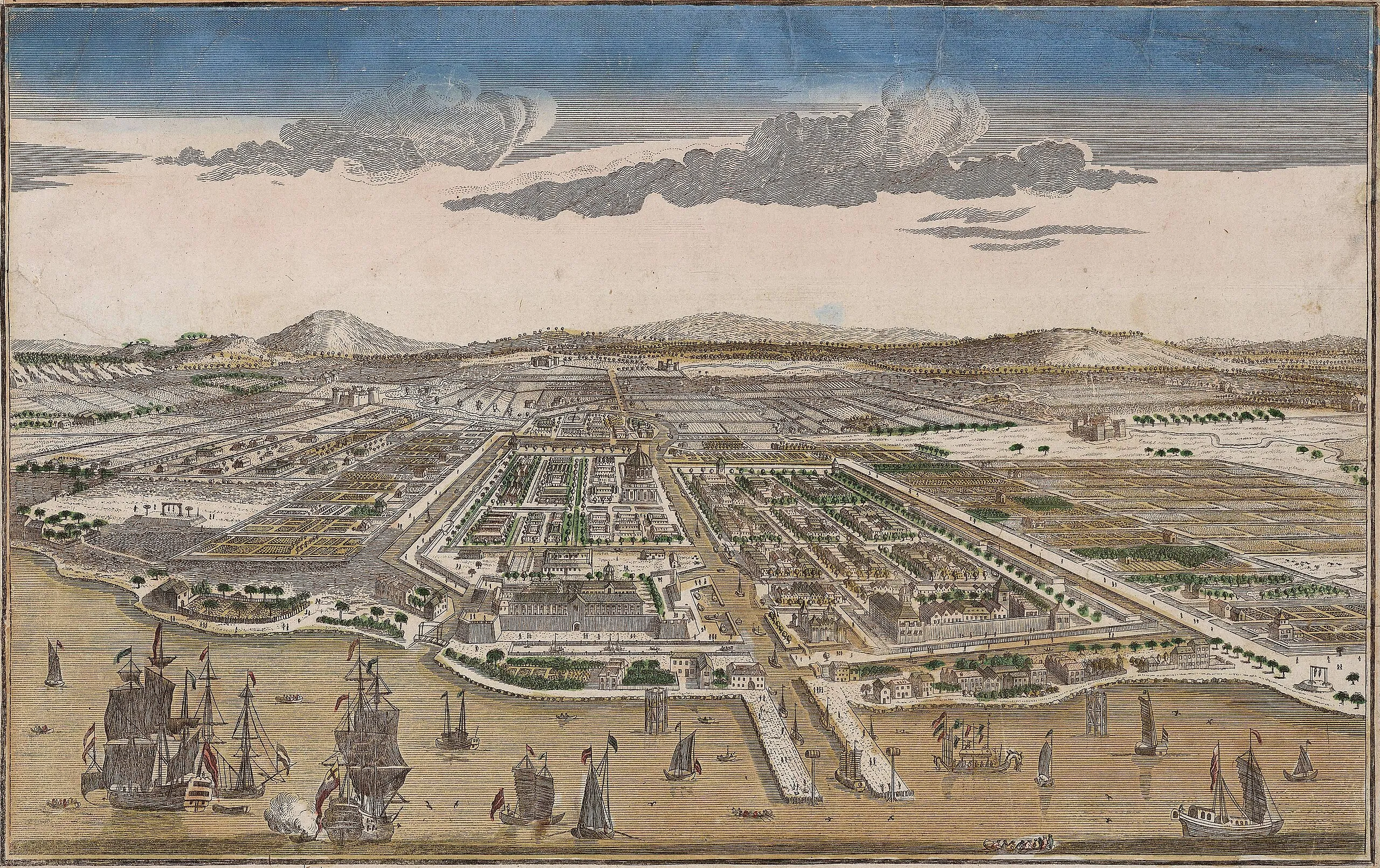

View of the Dutch city of Batavia, 1780 (Source: Wikipedia)

View of the Dutch city of Batavia, 1780 (Source: Wikipedia)

In the late 16th century, the Dutch sought to challenge the Portuguese dominance of the European spice trade, and so, sailed to Indonesia and Malaysia in search of a place to establish a trade settlement. There, the Dutch negotiated with the local ruler, Prince Jayawikarta, to establish a trade settlement on the banks of the Ciliwung River. Over the course of the next few decades, this and surrounding Portuguese, English, and Dutch settlements engaged in near-constant bickering over who controlled the area, punctuated by wars with the various rulers of the Indonesian islands and Malaysia who actually ruled the land. By 1619, however, the Dutch had firmly rooted themselves in on Java, wiping out the residents of nearby Jayakarta, digging canals and building castles for their new city of Batavia.

Like every other Dutch colony, the new colony of Batavia was defined both by its drive for wealth and its utter disregard for human life. Batavia, from its earliest founding by Jan Pieterszoon Coen, was defined by slaughter and genocide, with Coen himself earning the title the “Butcher of Banda.” In 1621, in revenge for the local Banda people trading nutmeg with the English, Coen slaughtered 14000 of the island’s 15000 residents, enslaving the remaining thousand and repopulating the island with indentured Chinese labourers. Slaughtering indigenous peoples was, for him, part and parcel of the Dutch East India Company (VOC)‘s mission. In a letter to the VOC’s directors, Coen wrote:

“Your Honours should know by experience that trade in Asia must be driven and maintained under the protection and favour of your Honour’s own weapons, and that the weapons must be paid for by the profits from the trade; so that we cannot carry on trade without war, nor war without trade”

His very motto (“Despair not, spare your enemies not, for God is with us,”) demonstrates a single-minded ruthlessness and a sense that the act of slaughtering indigenous Indonesians was not only necessary to secure the profits of Dutch investors, but a divinely ordained act. If there is a shining example of the worst impulses of capitalism, it can be found in Jan Pieterszoon Coen.

Yet for much of Dutch history, Coen was regarded as a national hero. It was his actions that made Batavia profitable and which provided the fuel for the Dutch Golden Age. The monuments and wealth that the Netherlands is now built on were paid for with centuries of Indonesian blood. Dutch rule - first via the VOC and then via the Dutch government - in Indonesia would continue until Indonesia’s independence in 1949.

Dutch soldiers in Indonesia during the Indonesian Independence War (Source: Universiteit Leiden)

Dutch soldiers in Indonesia during the Indonesian Independence War (Source: Universiteit Leiden)

That nasi goreng was one of my favourite foods as a child is a product of this colonial legacy. I am Dutch, and I grew up eating Dutch cuisine, of which nasi goreng is now a fundamental part. Much like curry travelled back to the United Kingdom as people made their way to Europe, nasi goreng travelled to the Netherlands with both former colonisers and the formerly colonised. It spread to the Dutch colonies, becoming endemic in Surinamese cuisine as well, reshaping the cuisines of countless people. That my mother participated in nasi goreng cooking contests is a product of colonialism. That I am able to make the dish as it should be made - loaded with spices and ketjap manis - from northern Europe is a product of colonialism.

That I have the stable internet and a laptop and the time to write this post is a product of colonialism.

Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia did not end with a whimper and a handshake. The Dutch war to prevent Indonesia’s independence was a brutal and bloody struggle, incorporating war crimes and genocide throughout the Netherlands’ struggle to prevent Indonesians from exercising their self-determination. That it happened immediately after WWII is not a coincidence - Indonesians suffered harsh treatment under the Japanese occupation of Indonesia during WWII and felt abandoned and exploited by the Dutch, fuelling a drive for independence. That Indonesia has suffered a long string of coups, genocides, and collapsed drives for democracy is, too, a product of colonialism.

In every dish I make, I try to learn a bit about the culture and the people that created it. In the story of nasi goreng, there is a story that is reflected time and time again across all of humanity. There is the nuance of human experience, and there is the reality of colonialism and the brutal cost of capitalism, not only in the short term, but in the long term. My life and how I came to be is rooted in Indonesia, even if neither I nor any of my ancestors have been there. We are able to be here because of the blood and the fruits and the spices of Indonesia.

Nasi goreng is the unified drive of Indonesia, and it is the root and soul of the modern Netherlands too.