Vegan Oil Down

Ingredients

1 onion, diced

3 cloves garlic, minced

3 potatoes, peeled and chopped

2 carrots, chopped

4 cups (250g) spinach, chopped

1 bell pepper, chopped

2 chili peppers, chopped

1 can pulled jackfruit

2 cups (500ml) coconut milk

2 cups (500ml) vegetable broth

2 tbsp paprika

2 tbsp turmeric

1 tbsp thyme

1 tbsp chives

1 tbsp oregano

Instructions

- Heat oil in a large pot over medium heat. Add the onions and garlic and saute until translucent (~5 minutes).

- Add all remaining ingredients. Bring the pot to a boil, cover, then lower to medium heat. Cook for thirty minutes, or until the potatoes and carrots are soft.

A longer and more detailed description

Remember last week’s moussaka recipe? Remember how much of a headache that was, and how many dishes and how much effort it took? I’m not going to say this is an apology, but this might be an apology.

Find a large pot. It doesn’t have to be your largest pot - this isn’t a soup - but it should be a reasonably large pot. Heat some oil in it, then add your onions and garlic to the oil. Cook them until you feel like they’re probably cooked, then add literally everything else. Dump it in, helter skelter. Spurt coconut milk everywhere. Glop in the jackfruit. Run absolutely wild on that pot and its contents until you feel you’ve made your point, and your tiny corner of chaos is complete. Bring it all to a boil, then lower to medium heat, and wander off to do something else until it’s done. Enjoy!

Substitutions and suggestions

For the potatoes and carrots - Oil down is meant to be made with breadfruit, but I, living in the Netherlands, do not have access to breadfruit. If you do, use that instead. Or you can use potatoes and carrots if you prefer them, but just know they’re not authentic.

For the spinach - Again, these are subbing in for an ingredient I don’t have, namely, dasheen leaves. Spinach is a much closer substitute than potatoes are for breadfruit, but again, if you have access to dasheen, use that.

For the jackfruit - This is subbing in for salted fish. If you do not like jackfruit or want something saltier, you could try mushrooms instead, or check out what I did for saltfish in my Antiguan recipe.

For the turmeric and paprika - This is subbing in for yet another ingredient I do not have, annatto oil. I suspect you could substitute in annatto here as well. Just be sure to be liberal with it.

For the chili peppers - I used lombok, as always. However, any chili pepper should work here.

What I changed to make it vegan

Oil down is traditionally served with some sort of salted meat. I swapped out the meat for pulled jackfruit to get some of that meaty texture, but did not salt it.

What to listen to while you make this

There is an entire genre of music native to Grenada called soca, and I love it. Temptress’ Pan and Jab is a great introduction to just how much fun it is.

A bit of context for this dish

CW: This post discusses slavery and the conditions under which enslaved persons lived.

Grenadian cuisine is similar to many other Caribbean cuisines. It’s based on local fruit and vegetables, copious amounts of seafood, and - due to the historical legacy of slavery - salted and preserved meats. Grenada, however, is unique in its use of spices and which specific spices it uses. While the use of spices is by no means unique to Grenada, the prevalence and variety of spices used in Grenadian cuisine is a reflection of the island’s unique history and importance in the Caribbean colonial economy. It is also a phenomenal example of how economies impact human behaviour.

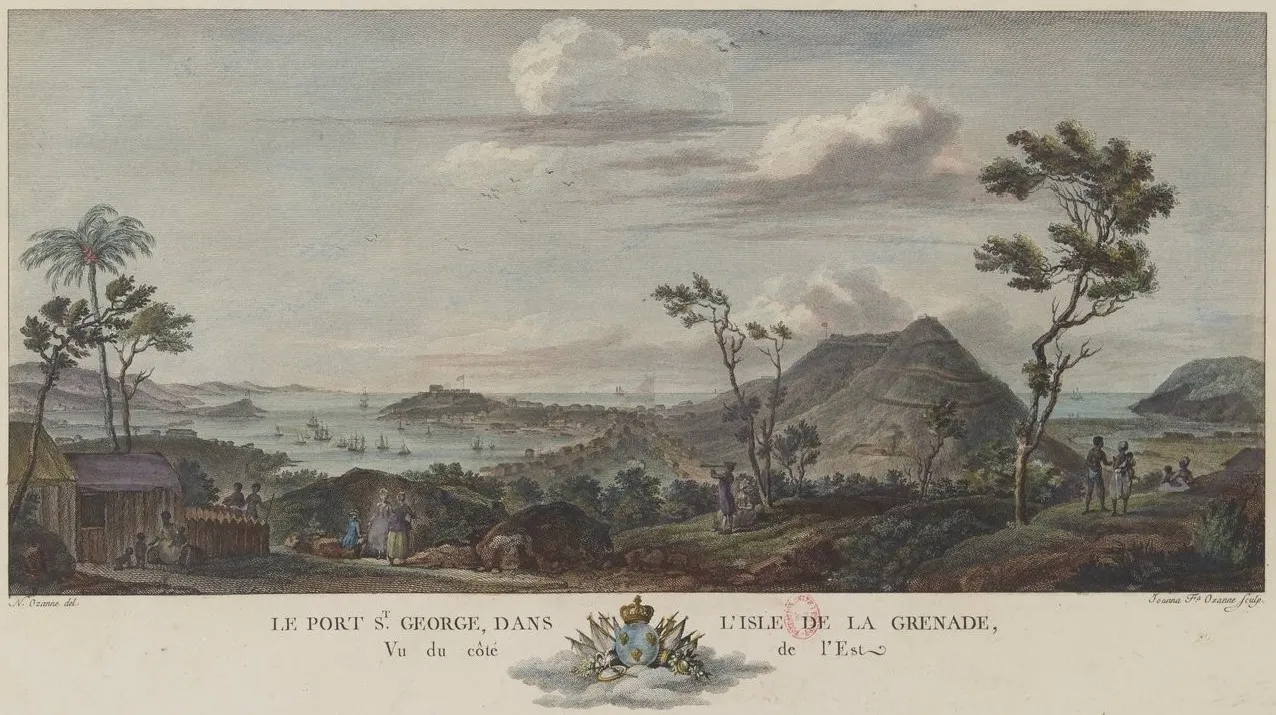

Port St. Georges in 1776 (Source: Wikipedia)

Port St. Georges in 1776 (Source: Wikipedia)

Grenada, like many other Caribbean islands, was initially settled by indigenous Americans, likely as early as 3500 BCE. However, with the arrival of Europeans, the majority of these indigenous Grenadians were wiped out through a combination of war, disease, and genocide. In the case of Grenada, that genocide was conducted at the hands of the French who, in 1649, established a colony, and proceeded to fully subjugate it by 1654.

While the Grenadian economy was initially based on sugar cane and indigo, cocoa became more popular and profitable with the introduction of cocoa beans in 1714. By 1763, the population of Grenada numbered over 15000, with the majority of the population being enslaved Africans kidnapped from Africa specifically to work on the sugar cane and cocoa plantations.

In describing the agricultural conditions in which enslaved Africans worked as “plantations,” however many connotations there may be in that word, it is still worth being reminded of what conditions were actually like. Records from Grenada are some of the most complete in the Caribbean, and reflect some of the interesting peculiarities of being a smaller, less profitable island that nonetheless housed wealthy plantation owners. Women, for example, were the primary field workers, and were expected to meet unreasonable quotas. When they failed to do so, they were beaten and flogged. Part of the justification for this by white slaveowners was the idea that, as Black women, they were naturally in a subjugated position, not only being seen as racially inferior to whites, but as inferior to men due to perceptions of polygyny in west African cultures. They were valued less than men, beaten more frequently, and died at a higher rate, leading to a harsh gender imbalance. When women gave birth, overseers were encouraged to find ways to kill the infant so the mother’s labour wouldn’t be diminished by having to care for a baby.

Enslaved women in Grenada, faced with these conditions, frequently chose not to have children. This included not only using natural forms of birth control available to them but, when confronted with pregnancy, having abortions rather than bringing children into the slavery system. By the early 1800s, the enslaved population of Grenada was decreasing, as women collectively refrained from having children.

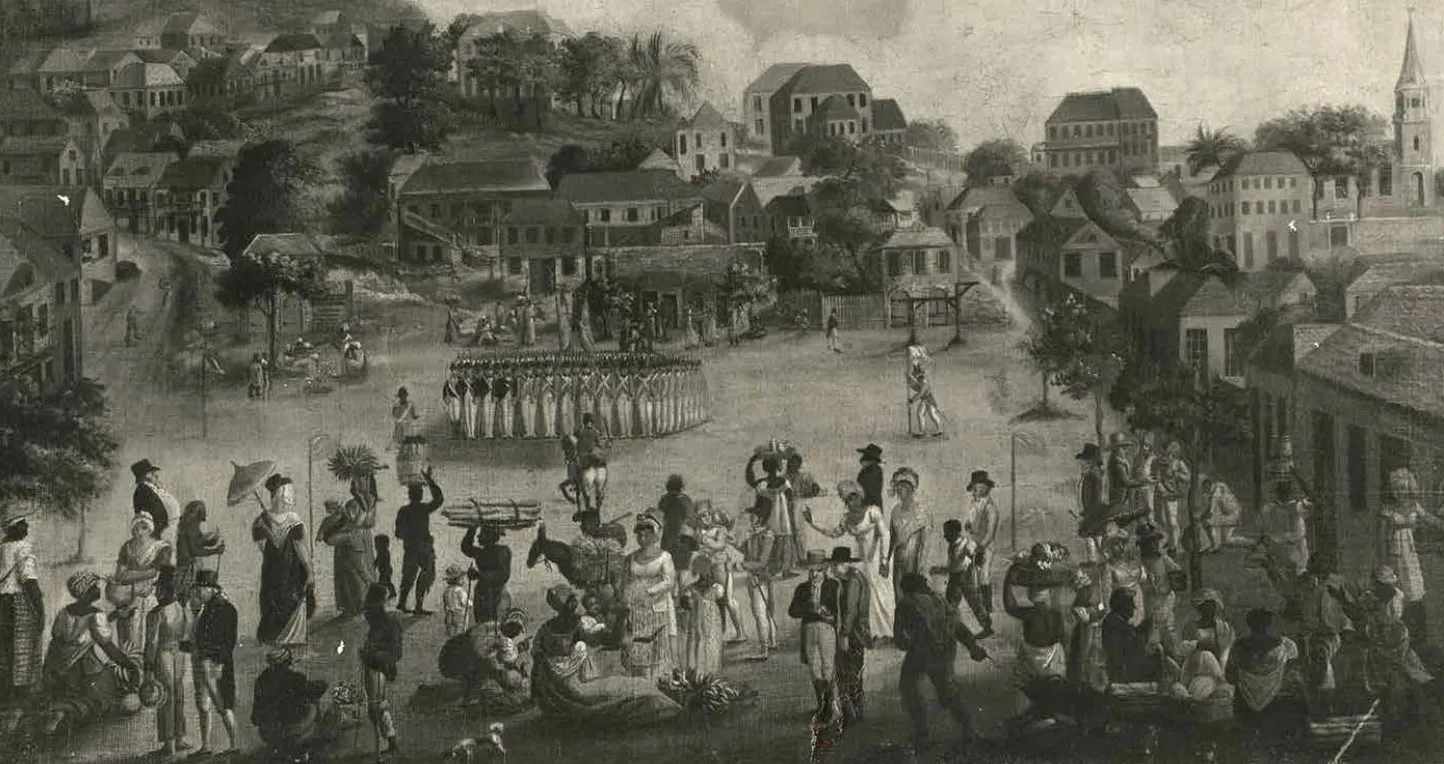

Enslaved people dancing (Source: Grenada National Museum)

Enslaved people dancing (Source: Grenada National Museum)

By the early 1800s, the lack of enslaved children on Grenada was increasingly being seen as a crisis, but one which the ruling elite were unwilling to take steps to mitigate. While the value of women increased, and while their work hours were shortened, no attempt was made to increase their available food, to the point where malnutrition was rampant among enslaved populations. Diets were primarily what enslaved persons could grow on little plots of land, occasionally paired with salted or dried meat. In some cases, this was so insufficient that enslaved Africans ate rotting meat to stave off starvation. What children were born often died not long after birth, either through violence, starvation, or disease.

For their part, white slaveowners recognised the demographic crisis confronting them, while remaining utterly oblivious as to how to mitigate it. Laws passed by the British Parliament to improve the living conditions of enslaved people were begrudgingly implemented at best and often ignored as slave owners believed that improving enslaved persons’ living conditions would leave them less afraid of slave owners.

Others believed enslaved women’s lack of fertility was a racial deficiency, with one doctor commenting:

“The negro women are not so prolific as the women in this country [England] which I apprehend to be owing to excessive and promiscuous intercourse with the other sex, and that commenced at a very early period, from this cause, they do not in general breed till a pretty advanced age, when they are not so much of objects of desire with the men; therefore a great part of the most proper time for the propagation of the species is totally lost.”

Rather than recognising the fundamental humanity of women and the inhumanity into which they were expected to bring children, white elites chose instead to blame women for an impending demographic collapse. The population of Grenada continued to decline every year until the abolition of slavery in 1834.

St. George's market square (Source: Grenada National Museum)

St. George's market square (Source: Grenada National Museum)

Though enslaved, women remained powerful arbiters of their own destinies. The enslaved women of Grenada were consistently described as “troublesome” by white slaveowners as they struggled to respond to women’s resistance to enslavement. Women often rebelled against slaveowners through arson, feigned illness, theft, self-mutilation, poisoning and murdering slaveowners, and escape. One of the largest slave rebellions on Grenada was fuelled by women smuggling weapons and supplies from under the noses of slave owners.

Others chose to resist through suicide, preferring death to living in a system of slavery. Much like the women furtively seeking abortions and refusing sex, non-existence was seen as preferable to a life spent in horrific deprivation.

Women have always been powerful. Even in the most degrading and horrifying of situations, women remain powerful.

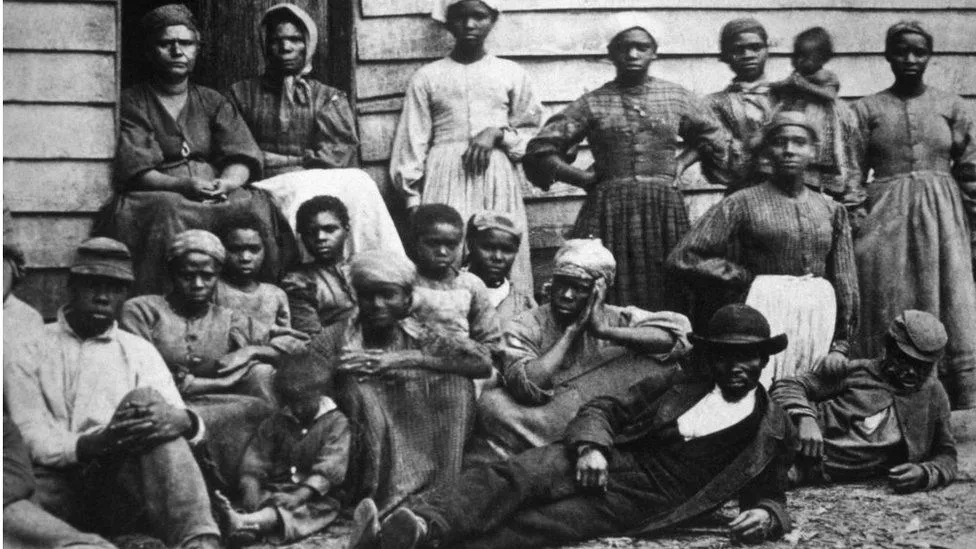

A group of formerly enslaved persons in Grenada (Source: BBC)

A group of formerly enslaved persons in Grenada (Source: BBC)

Agriculture continues to be one of the fundamental elements of the Grenadian economy, though now it’s nutmeg rather than sugar. Grenada produces 20% of the world’s nutmeg, with 30% of the island’s population relying on the spice for their income.

The difference now, however, is that people choose to grow nutmeg. They own their own farms, and they are proud of their work.

With power returned to the people, now, the farms and the future are their own.