Vegan Poutine with Bannock

Ingredients

Bannock

3 cups (360g) flour

1 packet (roughly 2.5 tbsp) baking powder

2 cups (500ml) hot water

Oil for frying

Poutine

3 tbsp vegan butter

3 tbsp flour

1.5 cups (375ml) mushroom broth

1.5 tbsp soy sauce

1 tsp dried thyme

1/2 tsp garlic powder

1/2 tsp black pepper

Vegan mozzarella

Instructions

-

Mix flour and baking powder in a bowl. Slowly add hot water, stirring throughout. Once all the water is added, mix to combine.

-

Set the bannock dough aside for at least ten minutes.

-

While the dough is settling, prepare your poutine. Melt the butter in a small pot over medium.

-

Once the butter is melted, add flour. Lower heat and mix to form a paste.

-

Slowly add the mushroom broth, mixing continuously. Ensure the gravy remains smooth throughout.

-

Add the herbs and spices, then let simmer until thickened, stirring occasionally.

-

As the poutine thickens, fry the bannock. Heat oil in a pan over medium-high heat. Form the dough into small balls, then flatten them into roughly palm-sized discs.

-

Fry until golden brown on both sides (~3-5 minutes/side). Set aside on a paper towel to dry.

-

Just before serving, add vegan mozzarella to the poutine to taste.

-

Serve the poutine over the bannock.

A longer and more detailed description

Go on, say it. You’re thinking it. I know you’re thinking it. Let’s just get it out in the open together.

This isn’t really poutine.

There. Now that it’s been said, do we all feel better? I know I do. Let’s make this anyway.

I’ll go into more of why I’m making this dish this way in the context, as well as an explanation of what bannock is, but for now, let’s start by making the bannock dough. Sift your flour and baking powder together into a nice, mysterious white powder. Slowly add your hot water, making sure to take the time to be delighted by the fizz the baking powder makes as it gets hit with the water. Is it wonderful? Of course it is. Take the time to enjoy the little things. Speaking of time, this dough now needs it, so set it aside, and start eying your one hundred percent accurate, please don’t at me, Canada, poutine.

Start by making a roux. I know that’s not what the briefer version of these instructions says, but you can feel all fancy as you proudly announce to your partner that the basis of this recipe is a roux. It’s much fancier than chanting “butter and flour in equal proportions” to yourself as you watch butter melt. Just say you’re making a roux and feel like a real chef as you do so.

Because, to be clear, you are a real chef. You’re cooking something for yourself that will be delicious, and that makes you a chef in my book. You go, you amazing human. :)

Once you’ve made a roux, slowly add your mushroom broth, stirring constantly as you do so. You want to be making a gravy, so the consistency of the broth and roux should be thick and not lumpy. If at any point, it becomes lumpy, pause, give everything a good stir, and keep going. This is an exercise in patience, but I believe in us both.

Once the broth is added to the roux and everything is nice and smooth, de-smoothify it by dumping in your herbs, spices, and soy sauce. All of these can be added to taste, but I assure you that everything is tastier when it is more. This is just a general rule of food. Mix it all up again, then set aside to simmer and thicken. Remember to stir it every so often, mostly when you get bored while frying the bannock.

Now that your bannock has risen (praise be), form it into small balls, then smash those balls between your palms into roughly palm-sized discs. Add these to your oil that you heated over medium-high heat, and watch them sizzle and brown. Once one side is brown, give them a flip, and fry the other side. Ideally, these should also rise a bit as they cook, but it’s fine if they don’t. They’ll still be delicious.

Once all your bannocks are cooked, turn your attention one final time back to the poutine. Add however much mozzarella you feel is appropriate (I added one handful), then mix it all again. Drench your bannocks in gravy, and serve. ᖁᕕᐊᒋᔭᕋ, bon apetit, and enjoy!

Substitutions and suggestions

For the bannock: Poutine should actually be served over french fries. You could, in theory, skip the entire bannock section of this recipe and just get french fries. I guess.

For the mushroom broth: Vegetable broth is fine here too, even if it’s less delicious.

For the shredded mozzarella: This will be much better and more accurate if you find a block of vegan mozzarella you can just chop up and drop into the gravy. I could not find that, so I went with shreds, which was passable, but not great.

What I changed to make it vegan

Everything. I changed everything.

Well, not everything. Poutine is not exactly vegan to begin with. I replaced the butter with vegan butter, worcestershire sauce with soy sauce and vegetable broth, and cheese curds with a half-assed attempt at mozzarella. I changed most of it, but many substitutions are reasonable ones.

For the bannock, there are many, many versions of bannock. I based my bannock on an Inuit recipe I found for reasons that will make sense to anyone who found this blog via the Jovian Symphony. I did not, however, add in or cook with lard or milk, ingredients that are found in other iterations of bannock. I kept it simple, delicious, and vegan.

What to listen to while you cook this

I’m going to start you off with “Child of the Government” by Jayli Wolf, and then move you on to the collected works of Tanya Tagaq. For reasons.

A brief context for this food

CW: This post discusses genocide.

Canadian cuisine, like the cuisine of many countries with large immigrant populations, is an amalgamation of a wide variety of cuisines and culinary traditions. Much like with Australia, trying to argue that there is any one particular “Canadian cuisine” is difficult, especially given the unique character of Canada of not only being a melting pot, but one that respects differences, and the continuation of culture.

This doesn’t mean there haven’t been attempts to describe Canadian cuisine, though. In his paper “Structural Elements in Canadian Cuisine,” Hersch Jacobs points out that what makes a national cuisine is less any particular national tendency towards a cuisine, and more an active assertion that this is the cuisine that will be associated with a particular identity. How true that is - especially given examples like Cambodia - is debateable, though Jacobs does still provide an interesting framework for contextualising what might be considered “Canadian cuisine.” Canadian institutions, he argues, promote a particular idea that there is a Canadian cuisine, and in so doing, engage in that act of creation. It’s essentially the “if you wish it hard enough, it will come true” approach to food, and I’m here for it.

What then is Canadian cuisine? Canadian geographer Lenore Newman suggests that it’s defined by five elements: seasonality, multiculturalism, use of wild foods, regional variations, and the prioritising of specific ingredients over recipes. I’d again argue that this describes most countries’ cuisines, but the point is still made that Canadian cuisine is a nebulous concept, but that that nebulousness doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

i know there's more to canada than tim hortons i promise i do

i know there's more to canada than tim hortons i promise i do

If cuisine is a crafted thing, then it’s worth considering who is doing that crafting. There have been a number of polls done, asking Canadians about their cuisine, and what they consider to be the national dish of Canada. Increasingly, poutine tops that list, with it and maple syrup being seen as the symbols of Canada. Given poutine’s humble beginnings in 1950s Montreal, this would seem like a triumph for the little dish, a la sachertorte or the various Belgian friet sauces. The reality, however, is much different, with many Quebecois viewing the “Canada-isation” of poutine as a form of cultural appropriation by the Anglophone majority. The origins and identity of bannock lead to a similar question of who gets to decide a cuisine’s identity, though with bannock, the food hasn’t reached the same ubiquity as poutine.

All of this leads me back to that question - what is Canadian cuisine? Is there a point at which a melting pot ideology shifts into cultural appropriation, and if so, where is that?

And trust me - I absolutely understand the irony of someone who writes this, sings in Inuktitut, and adds macadamias to Anzac biscuits talking about cultural appropriation. I am ready for the endless scorn you’re about to rain down upon me. Bring it, oh ye of the internet. I am prepared.

Let’s start by diving into the element of this dish I haven’t focused on yet, the bannock. Bannock is a nearly universal First Nations, Inuit, and Metis dish, though how it is prepared and viewed varies from group to group, and even person to person. Bannock of some sort has likely been part of Indigenous cuisine for centuries, if not millennia, with pre-Columbian bannock likely being made with lichen, acorns, camas, and similar native vegetation. The name “bannock,” however, comes directly from the contact First Nations had with Scottish traders, with the recipes for bannock changing to match newly available ingredients, such as flour.

A modern version of black lichen bread (Source: amazing-food.com)

A modern version of black lichen bread (Source: amazing-food.com)

In these initial contacts, bannock was seen as a convenience food. The simplicity of its ingredients made it easy to make while on the go, and the portability of the end product made it ideal for carrying while travelling or hunting. It made its way along both Indigenous trade routes and newly established fur trade routes, spreading across North America.

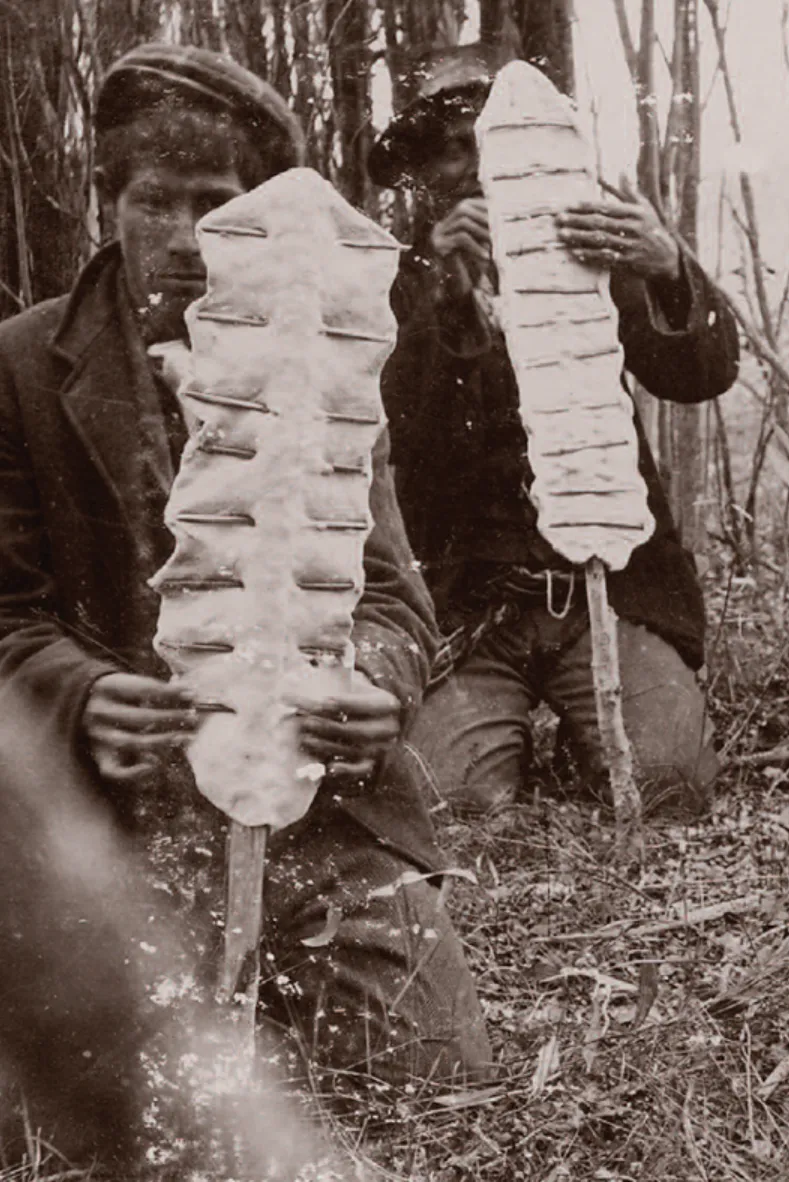

Metis men with bannock around 1900 (Source: Alaska Ethnobotany at KUC)

Metis men with bannock around 1900 (Source: Alaska Ethnobotany at KUC)

However, bannock is also ubiquitous for another reason. In 1876, the Canadian government passed the Indian Act. While not the first act to strip First Nations of their land, it was another blow, pushing Indigenous peoples to reservations, and removing them from their traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering grounds. There, instead of being able to pursue their traditional ways of providing for themselves and their families, Indigenous peoples were given rations of flour, milk, lard, and sugar. The only food now available was bannock. Rather than being a food of convenience, it instead became a food of survival, and a symbol of the mass dispossession that characterised the Canadian Indigenous experience.

It would be easy to say that bannock as a survival food is a thing of the past, and that, like a-ping, it is now embraced as part of a robust and resilient cuisine. This would also not be true. One quarter to half of Indigenous children in Canada live in poverty, with some not having access to running water or electricity. The destruction wrought to communities by forced displacement, cultural genocide, residential schools, and the forced abduction of thousands of children continues to resonate and reverberate throughout Indigenous communities. While the Canadian government apologised for the residential schools in 2008 and conducted a truth and reconciliation commission, this is a far, far cry from the justice that is long overdue for Indigenous communities. Bannock, as a means of survival, is not just a relic of the past. For many Indigenous people living on reservations and in the poverty imposed by colonial forces, it continues to be a survival food. Its status as a survival food also means it and what it represents has overwritten pre-contact culinary traditions, with many traditional foods being lost or inaccessible, replaced by the food of the colonisers. Bannock’s status in the Indigenous culinary canon is controversial, where it is simultaneously a comfort food serving as a reminder of a simpler time in a grandmother’s kitchen, and a reminder of the culture and people who have been lost beneath the boot of colonialism and white supremacy. Its universality reflects the universality of the Indigenous experience of displacement, violence, and genocide.

A map of (known) mass grave sites at Canadian residential schools (Source: Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada)

A map of (known) mass grave sites at Canadian residential schools (Source: Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada)

This brings me, weirdly, to poutine.

Poutine, to be clear, does not have anywhere close to the same origin as bannock. Poutine likely originated in one of three restaurants in Centre-du-Quebec - Le Lutin qui rit in Warwick, where it appears on the menu in 1957; Le Roy Jucep in Drummondville, where it was being served in 1958 and appeared on the menu (albeit with a different name) in 1964; or Le Petit Vache in Princeville, where a combination of cheese curds and fries appeared on the menu by the mid-1960s. The Canadian Intellectual Property Council certified Jean-Paul Roy, owner of Le Roy Jucep as the inventor of poutine, but, food history is rarely so easily resolved.

What is clear, however, is that poutine was invented in Centre-du-Quebec in the late 1950s or early 1960s. It is a Quebecois dish, with its name being based in Quebecois slang, and its origins being uniquely Quebecois. There is also the reality that, until fairly recently, it was a source of scorn and mockery on the part of non-Quebecois to the point where some Quebecois distanced themselves from it.

Political cartoon from the 1995 Quebec independence referendum depicting Quebecois as a "poutine race." (Source: Erudit.org)

Political cartoon from the 1995 Quebec independence referendum depicting Quebecois as a "poutine race." (Source: Erudit.org)

Quebec’s relationship with Anglophone Canada is complex, to put it mildly, and the relationship of Quebecois with their Anglophone neighbours moreso. Prior to the enactment of Bill 101 in 1977, Anglophones in Quebec earned higher wages than their Francophone counterparts, and there was a fear within Quebec that their unique identity would disappear under the auspices of assimilation. How valid these fears were (or are) is difficult to say, nor do I claim to speak on any Francophone’s behalf. New Brunswick has a thriving bilingual population of Acadians, while the Francophone population of Ontario has been more or less assimilated into the Anglophone one. Which future might have awaited Quebec if it hadn’t implemented Bill 101 (if either) is impossible to say.

The reality, though, is that Quebec has a unique identity and is fiercely protective of that Quebecois identity, especially against what it sometimes sees as a colonising Anglophone presence. Poutine became a symbol of Quebec, initially negative, but as one that has been increasingly reclaimed, especially by younger Quebecois. While not a poverty food, poutine’s journey from a mocked food to the symbol of a nation traces a similar path of rising to become something new, and leaving, to a certain extent, its past behind.

Source: Ottawa Poutine Fest

Source: Ottawa Poutine Fest

This brings me back to cuisine, cultural appropriation, and who gets to shape the narrative.

One of the controversies surrounding the “Canada-isation” of poutine is that question of whether Canada as a nation gets to claim a dish so intimately linked to Quebecois identity. Quebec may be physically part of Canada, but as recently as thirty years ago, its people came extremely close to severing their ties with Canada and becoming an independent nation. While the Canadian government recognise Quebec as its own entity in 2006, there is still that question of what being Quebecois means and how that relates to being Canadian. A similar question can be asked of Indigenous communities, many of whom have far fewer recognition and rights than the Quebecois. Who gets to shape the narrative of Canada, and of Canadian cuisine? Whose stories get acknowledged, and whose get assimilated into the grand narrative?

When thinking about what cultural appropriation means and how it manifests, I think about examples of that conversation, and what happens around them. There is, on the one hand, theft without acknowledgement. This is the removal of a piece of culture from its context, a rebranding, and a re-presentation with no acknowledgement that it came from somewhere else. It’s plagiarism on a cultural scale, and it is abhorrent and bordering on racist. There is also the racist appropriation of imagery, symbology, and names, done with an intentional lack of respect for these symbols’ origins, and with an intention to exotify and dehumanise those whose culture has been stolen. Then there’s a vaguer form of appropriation, done with appreciation and acknowledgement by people not of that culture, but while still trying to include that culture in the narrative. I would argue that this latter example is not appropriation, but rather, part of the cultural exchange that characterises the entirety of human existence. Where poutine and bannock and their place in the Canadian cuisine canon fit within these categories, I can’t say. Some is likely appropriation without acknowledgement. Some likely isn’t.

I combined poutine and bannock because, to me, they tell a similar story of who gets to be part of an identity and who doesn’t, of whose story becomes the narrative and whose doesn’t, and whose culture survives and whose doesn’t. Both also represent something quintessentially Canadian, not just in their origin, but in that sense of combining new things in new ways, and trying to preserve a way of life in the face of colonialism. They also fit that idea of Canada as a multicultural melting pot, acknowledging and celebrating one another’s differences, and combining them into something new.

Cuisine and culture are what we make of them, and though I am not Canadian, I hope my interpretation of what that means still fits within that idea of what it means to be Canadian.