Vegan Soup Joumou

Ingredients

1 small pumpkin, chopped

1 butternut squash, chopped

2 scallions, diced

5 cloves garlic, minced

2 potatoes, peeled and cubed

1 carrot, chopped

3 stalks celery, chopped

1 cup (150g) broken vermicelli

2 cups (500ml) vegetable broth

5 cabbage leaves, chopped

2 chili peppers, chopped

1 tbsp dried parsley

1.5 tbsp cajun seasoning

Salt

Pepper

Instructions

- Boil the chopped pumpkin until soft, then drain and blend until smooth.\

- Add the pureed pumpkin back to the pot and add vegetable broth. Mix until smooth, then bring to a boil.\

- Add all vegetables and spices. Cook until the vegetables are soft (~10 minutes). \

- Add the vermicelli and cook until ready (~7 minutes).

A longer and more detailed description

It is unfair to ask me to chop up both a pumpkin and a butternut. That is entirely unfair, and I strongly object. That said, if you want my advice on how to do this efficiently, do not chop the pumpkin in half first by raising your knife over your head and swinging it down while yelling “hi-YAH.” That is not helpful and may just end up splattering bits of pumpkin everywhere. Just so you know.

Regardless, that pumpkin does need to be chopped. The hardest part of this is getting through the pumpkin shell, but I believe in you. This is easier with a riper pumpkin, but - say it with me now - I live in the Netherlands and I take what I can get. Separate your pumpkin from its skin, then chop its flesh into little bits. Add those to a pot of boiling water and let them boil until they’re soft enough for your blender to handle.

You may be thinking that this is a good time to wander off and do something else with your day, but you’d be wrong. There is a giant pile of vegetables to chop, and one of them is a butternut squash. Chop as much as you can in the time it takes your pumpkin to soften - which, I’m going to warn you, is less time than you think it is - going in order of vegetables that need the most time to soften to least. Once you’ve made less progress on that pile than you’d like (mostly because of the butternut), drain and puree your pumpkin, then readd it to the pot. Add your vegetable broth, give it all a mixy mix, and bring it to a boil.

Are your vegetables ready? No? Too bad, they’re going in.

Add your vegetables, starting with the squash and root vegetables, then adding whatever’s ready when it’s ready. Add your spices, and then, finally, the vermicelli. Mix everything in, wait until the vermicelli is ready, then serve with some nice bread. Bon apeti!

Substitutions and suggestions

For the pumpkin - The pumpkin is the point. If I can’t escape it, neither can you.

For any other vegetable - This is a soup made primarily with root vegetables. I used the ones that I like, but feel free to sub in anything you think would be better, like turnips, radishes, or kale, if you’re weird. You can also leave out as many vegetables as you’d like - precise adherence to a recipe is not the point here.

For the Cajun seasoning - My Cajun seasoning has paprika, chili powder, and cumin. Adding those individually would likely have the same effect.

For a thinner or thicker soup - Feel free to add more or less broth (or more or less vermicelli, which is soaking up the broth) for a thickness to your liking. Again, precision is not the point.

For the vermicelli - You do not have to add this, but it adds a nice texture. You can also add a pasta of your choice.

What I changed to make it vegan

Soup joumou is ordinarily a meat broth. I didn’t want a meat broth, so I removed the meat entirely without substituting. However, part of the point as well is that the meat adds flavour to the pumpkin broth. To compensate, I substituted in vegetable broth and extra spices that wouldn’t ordinarily be in there, as well as extra garlic and scallions. I think it worked out pretty well.

What to listen to while you make this

May I introduce you to the fantastic work of Malou Beauvoir, especially “Rasenbleman?”

A brief context for this dish

CW: This post discusses slavery.

I can’t help but feel that many of the narratives in the recipes of the past few weeks have been building to this particular narrative. Like Guyana and the rest of the Caribbean, Haitian cuisine is very much shaped by a blending of influences and the pervasive realities of slavery. Like Ghana, the stories of these peoples are the stories of resistance and rebellion, and how those acts of revolution were inspirational the world over. Like Guinea, much of Haiti’s current economic state can be attributed to the sabotage of the newly established state by the French. This story is the other half of the story of Hispaniola and a further contextualisation of the Dominican Republic, but also, a celebration of independence and the ones who fought for it, much like Guinea-Bissau.

All the stories told so far about slavery, independence, revolution, resistance, and French colonial dominion culminate in Haiti.

And nothing tells the story of Haiti better than soup joumou.

Haitians during Carnival (Source: Ripthestigma.org)

Haitians during Carnival (Source: Ripthestigma.org)

I discussed much of the pre-Columbian history of Hispaniola in my article on the Dominican Republic. At the risk of being redundant, I recommend reading that article to understand both why Hispaniola is divided, and the long legacy of Hispaniola’s Indigenous peoples and Spanish colonisation. However, the story of these two nations diverges by the mid-17th century. Spain, focusing on its more profitable and less rebellious colonies on the American mainlaind, largely abandoned the western third of Hispaniola, allowing it to become a haven for pirates, primarily French pirates. These French pirates settled the island, growing tobacco and other crops, and encouraging other French farmers to join them. In 1697, the Spanish and French signed the Treaty of Ryswick, officially dividing Hispaniola. The Spanish ruled Santo Domingo, and the French, Saint-Domingue.

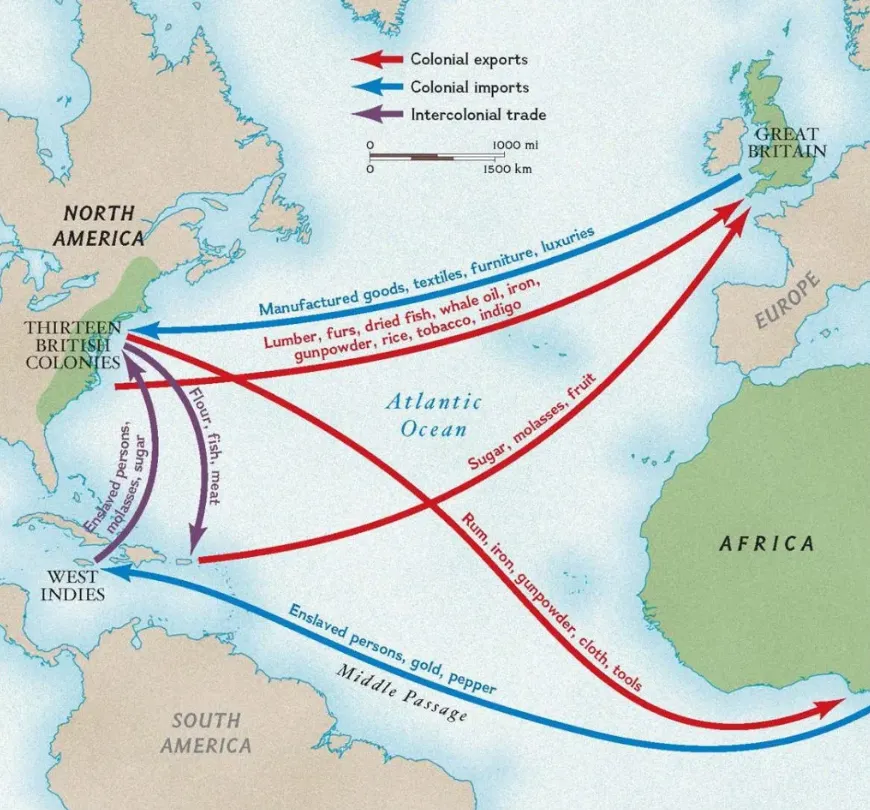

And, much like in the rest of the Caribbean, the French colonisers turned to the mass trafficking of people from Africa to draw profits from their new colony. Over the course of the next century, tens of thousands of Africans were brought to Haiti to farm sugar, coffee, and tobacco. By 1788, the population of Haiti included nearly 700 000 enslaved Africans, vastly outnumbering the population of white plantation owners and free people of colour. It was Haiti that supplied half of Europe’s sugar and coffee, all while over a third of new African arrivals to the colony died within a few years of arrival due to disease and brutal working conditions. Much like in Grenada, birth rates were low among the enslaved population, though the unique circumstances of both French slavery and Haiti itself meant that there was a unique blending between white and black populations.

Though, to be clear, while it was customary for a white plantation owner to have one or several enslaved “mistresses,” the dynamics of slavery are such that this was never a consensual relationship on the part of the enslaved women. While Haiti did have a significant population of mixed race children, these children were the product of mass, socially encouraged, rape.

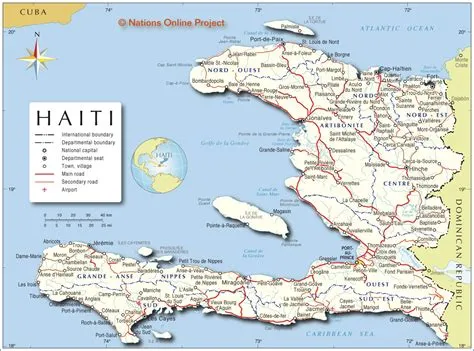

It's been a while since I brought out the map. As a reminder, though, all hail the map!

It's been a while since I brought out the map. As a reminder, though, all hail the map!

Throughout the decades of slavery, however, enslaved persons in Haiti were rarely passive. People continuously escaped enslavement, fleeing into the mountains of Hispaniola, where they took refuge either with Indigenous communities, or with growing communities of other escaped enslaved persons, known as maroons. These communities established self-sufficient practices while also remaining cognizant of the reality of slavery along the coast. These communities continued to rebel against French rule and organise raids into plantations. When revolution arrived in Haiti, it did so with significant support and leadership from maroon communities.

Sculpture of Francois Mackandal, a Maroon spiritual leader

Sculpture of Francois Mackandal, a Maroon spiritual leader

While Haitian slavery looks fundamentally similar to slavery across the rest of the Caribbean, its ending follows an entirely different track.

The roots and course of the Haitian Revolution are extremely complex, and this is, however I might pretend otherwise, a recipe blog. This is a broad strokes summary at best, and I highly recommend reading an actual book (or several) to learn more about the Haitian Revolution itself.

In brief, however: When the National Assembly in Paris published the Declaration of the Rights of Man on 26 August 1789, their declaration that “all men were free and equal” had likely been written without consideration for French colonies or the enslaved persons working on them. French planters and the Haitian middle class immediately began agitating for Haitian independence, seeing this declaration as a statement that they were equal citizens alongside their mainland counterparts.

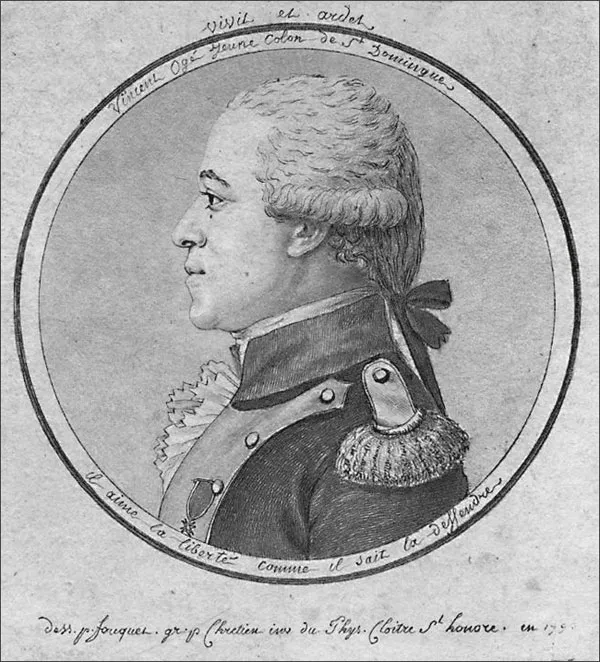

For free people of colour on the island, however, the Declaration meant something more - it was an opportunity to assert their full citizenship and their right to vote and be seen as equal members of society. For their part, the National Assembly heard the cries of the free people of colour, and in March 1790, granted the right to vote to all free people of colour in all French colonies. In Saint Domingue, however, the colonial authorities refused to enact the law, leading to a rebellion on the part of these free people of colour. In October 1790, Vincent Oge and Jean-Baptiste Chavanne led 300 rebels in a revolt against the colonial government, seeking to overthrow it and establish equality for free people of colour in Saint Domingue. By late November 1790, however, Oge was captured, and in February 1791, he was executed and his head impaled on a spike as a warning to other would-be revolutionaries.

Instead, however, his treatment served as the catalyst for a revolution unlike any the world had ever seen.

1790 portrait of Vincent Oge (Source: The Louvre online)

1790 portrait of Vincent Oge (Source: The Louvre online)

On 21 August 1791, a tropical storm rocked Haiti. In amongst the rain and lightning, several thousand enslaved persons gathered for a secret vodou ceremony. Seeing the tropical storm as a good omen, they rose up, massacring plantation owners as they slept. By 24 August, 13000 formerly enslaved persons controlled the Northern Province, burning plantations and killing white people. Within two months, there were over 100 000 rebels, and Haiti was thrown into a full-on civil war.

The monumental nature of what was happening on Haiti cannot be understated. While there had been slave rebellions throughout European colonies for centuries, they had never been as successful as this one. Within a few months, Haitian rebels had overthrown the European order, elicited a guarantee of the abolition of slavery from the French government, and killed thousands of former slave owners.

The importance of Haiti also didn’t escape the attention of surrounding European powers. Spanish and French troops arrived on Hispaniola, both to tamp down the revolution, and to claim Saint Domingue for themselves. There, they were defeated by the revolutionaries, with their leader - Toussaint Louverture - threatening that if the British did not withdraw from Saint Domingue, the revolutionaries would invade Jamaica. In 1801, Louverture declared Saint Domingue to be an autonomous Black state, ostensibly under French rule, but a state intended to be run by him for the population of now free Black people. In response, Napoleon invaded Saint Domingue. The revolutionaries burned the colony to the ground.

Over the course of the next year, Napoleon’s forces led by General Rochambeau (yes that one) and Charles Leclerc took back control of Saint Domingue, losing thousands of their own troops in the process. Louverture was betrayed and shipped to France to die in a French prison. Haitians on the island fought a brutal guerrilla war, with Rochambeau inventing a 19th century gas chamber to execute revolutionaries en masse.

In the end, however, Napoleon’s forces won, and for a few months, the French ruled Saint Domingue once again. One of their first orders of business was to reinstate slavery in the colony, and within two months, revolution broke out once more.

This time, faced with the total annihilation of his forces to violence and disease, Rochambeau surrendered. On 1 January 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared Haiti to be independent. All told, the war had cost at least 350 000 Haitians their lives.

But they were free. For the first time, a slave rebellion had successfully overthrown a European power and created its own, free state.

To celebrate, Haitians made and served soup joumou.

1802 engraving of Toussaint Louverture (Source: Wikipedia)

1802 engraving of Toussaint Louverture (Source: Wikipedia)

Throughout its time as a French colony, the people of Saint Domingue had cultivated local squash, known as “joumou” in Kreyol. These squash, however, were cultivated solely either for export or for the consumption of the elite. For enslaved Haitians, these were the epitome of the forbidden fruit. When the revolution was won, then, joumou symbolised freedom. Eating them symbolised victory over slavery and the freedom to eat and be whoever they chose to be. Haiti could, in that moment in 1804, become whatever it chose to be. Its economy was ravaged, its cities burned, but its people were free.

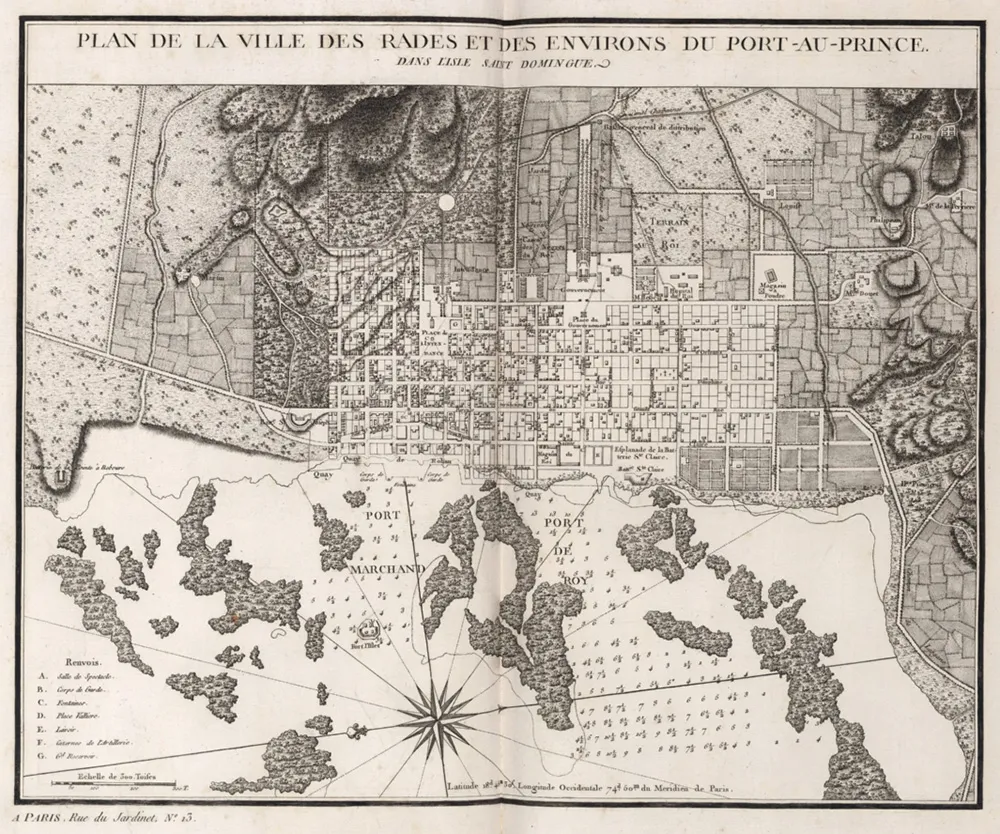

1804 map of Port-au-Prince (Source: David Rumsey Map Collection)

1804 map of Port-au-Prince (Source: David Rumsey Map Collection)

This is, of course, very, very far from the end of the story of Haiti. As with its later colonies, France did not relinquish control of Haiti. In 1825, Charles X demanded Haiti repay its “debt” to France or be invaded, a debt that ultimately cost Haiti more than $500 million to repay, not having repaid it until 1947. Repayment crippled the Haitian economy, and while it isn’t the sole reason Haiti is now the poorest country in the Caribbean, it is a significant contributor.

The Haitian Revolution also inspired many other revolutions throughout the Americas, with Louverture being a quintessential figure in Black liberation movements. It is because of the Haitian Revolution that the Louisiana Purchase happened, arguably fuelling the United States’ sense of manifest destiny.

But I like to think about that moment in 1804. I like to think about the formerly enslaved people, cracking open squash and celebrating by making soup. In that moment, they didn’t know the future. They had witnessed the brutality of revolution, but did not know its significance to history or what they meant to the world. What they knew was that they were free, and that freedom looked like soup joumou.

I’m not going to pretend the history of Haiti isn’t a complex and often tragic one. However, I think it’s also important to remember that identity is often a source of joy. Haiti is a deeply unique place with a unique and beautiful history. While a soup doesn’t sum up the lived experience of a whole people, understanding what it symbolises to make soup joumou and the statement of fighting back against oppression that it is is a powerful one.

Bon apeti.