Balatro

i don’t understand the discourse around balatro

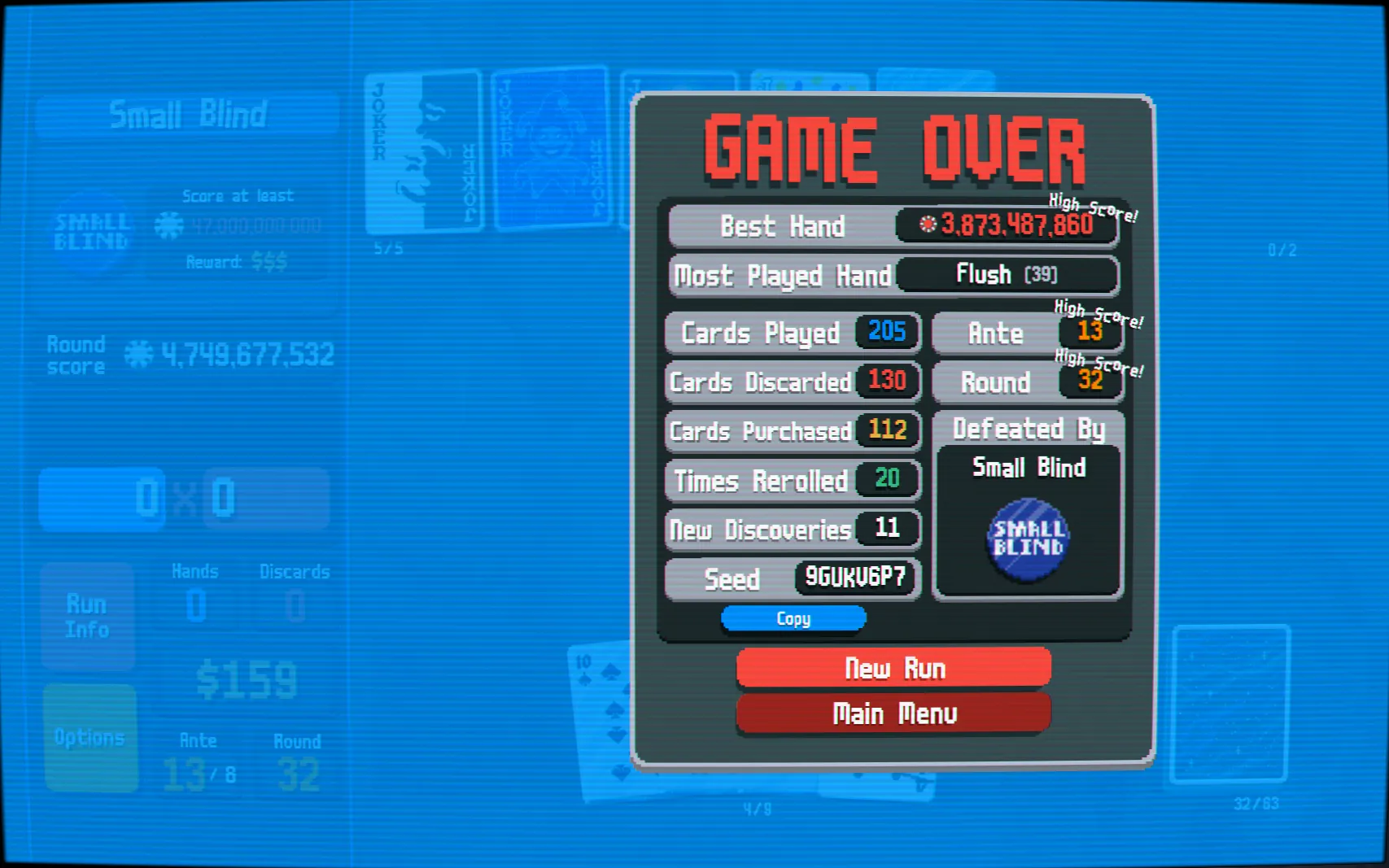

These screenshots are just going to be me proving I know how to play this game, and I need you to know that from the outset.

These screenshots are just going to be me proving I know how to play this game, and I need you to know that from the outset.

To be clear, this is not me saying I don’t understand Balatro. I understand Balatro very well, and, having put 32 hours into it as of this writing, I think I understand how to play it. Nothing about how to play Balatro or why it’s successful is baffling to me. It’s a fun little roguelike with a deceptively simple premise that allows for immense creativity in its mechanics and almost limitless replayability. It’s a good, well-made game, and I’m enjoying it.

But I’m not addicted. It’s not “video game crack.” Sure, I’ve put 32 hours into it, but that’s been over the course of a month, and because it’s a nice game to play over breakfast and it fills in the gap left behind by a game like Fairytale Fables. I’m not addicted, and I never will be because it doesn’t hit any of those addiction buttons for me.

So why, then, is the discourse around Balatro so centred around how addictive it is? What is this discourse, and why am I so far removed from understanding it?

I make numbers go brrrrrr

I make numbers go brrrrrr

For those (maybe three of you?) unfamiliar with Balatro, Balatro is a poker-themed roguelite deck-builder. You are handed a deck of cards - maybe an actual deck of cards, maybe one with all the face cards removed, who can say - and told to beat the boss eight times. Along the way, players can modify the deck and the hands they make with it by removing cards, adding cards, modifying cards, or picking up jokers that give different abilities or boosts. Hands are worth points, with the number of points required to beat a hand increasingly logarithmically as the game goes on.

And…that’s it. If you’re familiar with a deck of cards and the rough outline of poker, you have the knowledge you need to play Balatro. As with any deck-builder, it is, of course, more difficult to master than it is to learn, but it isn’t a deeply complex game. Anyone can play it, and, based on its sales numbers and the discourse around it, everyone is.

@_@

@_@

It’s an excellent game, and I’ve been enjoying it very much. It has hypnotic music and visuals that serve as a nice backdrop for the gameplay, and the variety of decks, jokers, and bosses available really do make every run unique. While I occasionally feel a bit stuck on a particular deck type or stake - it took me five tries to beat the abandoned deck, and I’m still salty about it - each run feels winnable from the outset, with the only factor being me and the decisions I make. It’s very much like every other roguelike deck-builder in that regard, in that the outcome, while not entirely up to the player, is largely the result of the player’s decisions. The process of playing and growing at Balatro isn’t a process of throwing myself at a gap and seeing if this time, I manage to somehow jump it. Instead, it’s a process of watching myself grow and learn the game, and the delight at realising I am actually improving.

But I’m not addicted. All the discourse around this game, everything being said about it highlights how addictive it is, and it’s just…not.

Sometimes the game is an absolute butt, though.

Sometimes the game is an absolute butt, though.

When I say Balatro isn’t addictive, it’s not coming from a place of me touting my self-control and perching on some all-mighty perch, judging others. Oh no, I get addicted. I get very addicted to games to the point that it becomes a problem. I understand addiction. If I’m honest, the discourse around Balatro being addictive kept me from going anywhere near it for months. I only got it because a friend gifted me a copy and then started asking me about my runs and what I was doing in them.

In my piece about gaming addiction, I explored the games I’ve been addicted to and what exactly got me addicted to them. Without rehashing that entire article, what fuels addiction for me is the ready accessibility of a game. It’s less that a game is easily playable, but more that it instils a sense of FOMO if I’m not playing it, and makes it easy to chain its play for day after day, pulling me in and reminding me of its existence, presenting me with a stage on which to excel, and then pushing constant reminders that I need to do my best to achieve that excellence. I’m addicted less to the game itself, and more to the habit and, to a lesser extent, the thrill of competition.

Balatro doesn’t hit any of those buttons. There is no trigger, asking me to log in each day. It exists on my desktop as a little icon, letting me know I can play when I want but also that I’m under no obligation to do so. Its rounds are long enough that I have to think consciously about my other commitments and make sure I have time for it before I load it up. It also requires enough thought and planning that I can’t zone out during it or multitask like I might with some of the other games I cited in that article. It’s a roguelike deck-builder in its purest form, and, though I love them, I’ve never gotten addicted to one. It’s an ideal game for discrete, controlled sessions, which is exactly how I’ve been playing Balatro.

The people getting addicted I suspect are not veterans of the genre like me. The people getting addicted are those for whom this is their first roguelike deck-builder, and who are unprepared for a game with a button that prompts you to try again.

no ragrets

no ragrets

My first roguelike deck-builder was Monster Train. I started playing it in 2021, and, as of this writing, have 388 hours in the game. Like Balatro, Monster Train can be beaten in discrete 45-60 minute runs, with each run being entirely separate from the others. There is no real progression (other than ramping up the difficulty), no greater narrative, nothing but you, your little collection of cards, and the enemies that need to be beaten. I loved it, and made it my absolute mission to beat it on the highest possible difficulty. Which I eventually did.

Monster Train drew me in both because of the promise of unique runs, but also because of how much the outcome of those runs was a combination of what artefacts and cards I drew and my own skill at recognising what to do with those artefacts and cards. Much like with Balatro, I saw a progression, not in the game, but in my own skill, with that skill manifesting in unlocking higher and higher difficulties. That it had discrete runs made it easier to walk away when I lost, but equally, made it easier to imagine that the next run might have circumstances a bit more tailored to my play style, and might therefore be winnable. I went through my phase of pulling Monster Train out when I wanted to fill a gap in time, but didn’t get addicted, because I understood how to walk away.

Monster Train was my introduction to roguelike deck-builders, and I’ve loved the genre ever since. I’ve reviewed many games from the genre, and have run my way through the big names in the space. When I pick up a roguelike deck-builder, it’s no longer my first time or even my tenth time. I’m not exposed to brand new mechanics and ways of thinking about gaming. I’m looking at a familiar friend with a new face, trying to decide if how it’s clothing itself today is a way that works for me.

But you also never really forget your first.

I am here to win, and win I shall.

I am here to win, and win I shall.

When I look at the screenshots included in the discourse around being addicted to Balatro, I always notice what people are playing. I look at what jokers they’ve chosen, what build they’re moving towards, what hands they’re playing, all the small things that tell me who they are as a player. While it’s not universal, what I see is hands that are on the third or fourth rounds, jokers that are not optimised, hands with better options if the player is just willing to gamble a tiny touch more. What I see in screenshots from people saying they’re addicted is not the hands I would play, but the hands of people for whom this is likely an entirely new type of gaming. I see people who haven’t played a roguelike deck-builder before, and who are learning the genre and having the same delight with it that I had when I first played Monster Train all those years ago. They are addicted and say Balatro is addictive, not because it is, but because this is their first time getting confronted with a “new run” button and that siren’s song of knowing they’re growing as a player.

Balatro has sold at least six times as many copies as Monster Train. Unlike Monster Train, its theme doesn’t centre around mechanics specific to the game or around its own narrative and character. Balatro has a very simple and accessible set-up of a modified poker deck. It doesn’t ask players to care about what a sage imp is or how it interacts with consumed cards in the context of a combination with a Stygian Guard combo. It hands over familiar tens, sevens, jacks, and kings, and says “have fun.” It has exploded into public awareness because of the deceptive simplicity of its poker theming combined with the reality that deck-builders are awesome.

The people who are addicted are addicted because they’re finding their first. I’m happy for them.

Developer: LocalThunk

Genre: Roguelike deck-builder

Year: 2024

Country: Canada

Language: English

Play Time: 45-60 minutes/run, unless you’re me, in which case, it’s either 5 minutes or 5 hours

Playthrough: https://youtu.be/Rl4xQKbo4eg