Booth: A Dystopia Adventure Review

There’s an old adage that, as a person ages, they become more conservative, that as they learn how the world actually works, they lose the idealism that defines youth, having it instead be replaced with realism and the crushing knowledge that this is all there is to life, and the best any of us can hope for is survival.

None of this is true for me. If anything, I’ve gone further to the left as I’ve aged, my political views and general attitude towards the world shaped by the knowledge that the world, though it is this way, doesn’t have to be, that I have, in my lifetime, seen it be better, and recognise the utter decline in quality of life caused in no uncertain terms by rampant capitalism. I was radicalised by the pandemic, forged in the crucible of public scrutiny, and have come out on the other side more resolute than ever that the greatest evil in this world is the continued existence of capitalism, and that, as long as it persists, humanity will continue pushing it and the planet it inhabits towards total annihilation.

So no, I haven’t mellowed with age. I’ve aged like cheese - sharper, less patient with others’ nonsense, and wanting only to be paired with a good wine.

All this is to say, then, that when I’m put in a position to play a fascism simulator and be a cog in the machine of a vast dystopian state, my thoughts are mixed. I, on the one hand, understand that depiction is not endorsement, that there is a world of difference between presenting a dystopian society and advocating for any element of that story. One the other hand, every story has basic assumptions within it, basic morality plays that factor into how the author or developer wants the player to think about what they’re consuming. It’s here that I struggle more and more when playing dystopian job sims and having to slot myself into the role of the reluctant fascist.

Which brings me to Booth.

As I said.

As I said.

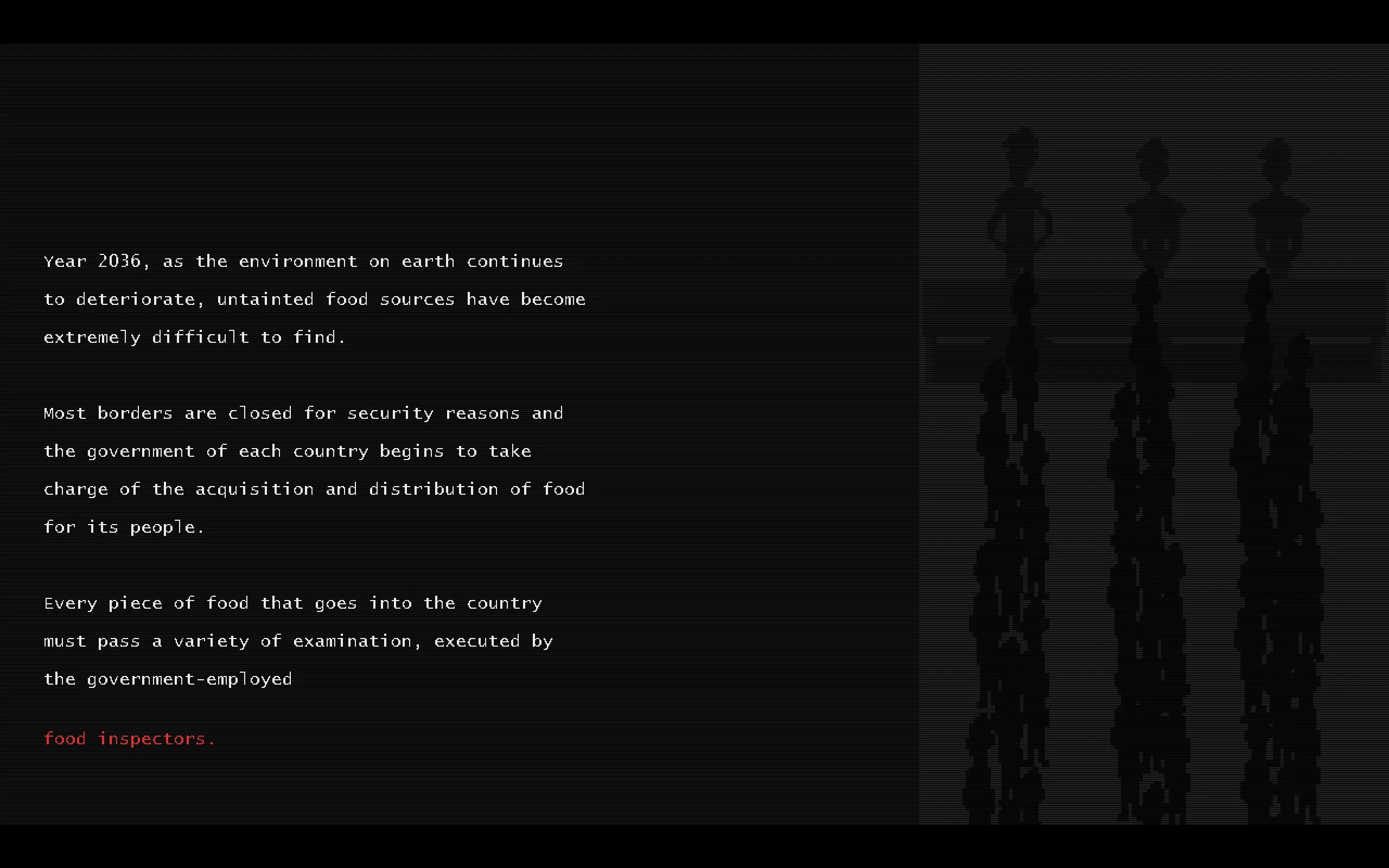

Booth is a dystopian job sim. Set in the year 2036 as climate change wreaks havoc on the world’s food supply, you play as Ned Crawford, a food inspector charged with ensuring the safety of the food bound for the city-state of Iden. While this job is considered cushy by Iden standards, given its full availability of food and liveable space, Ned dreams of freedom and of escaping the oppressive state.

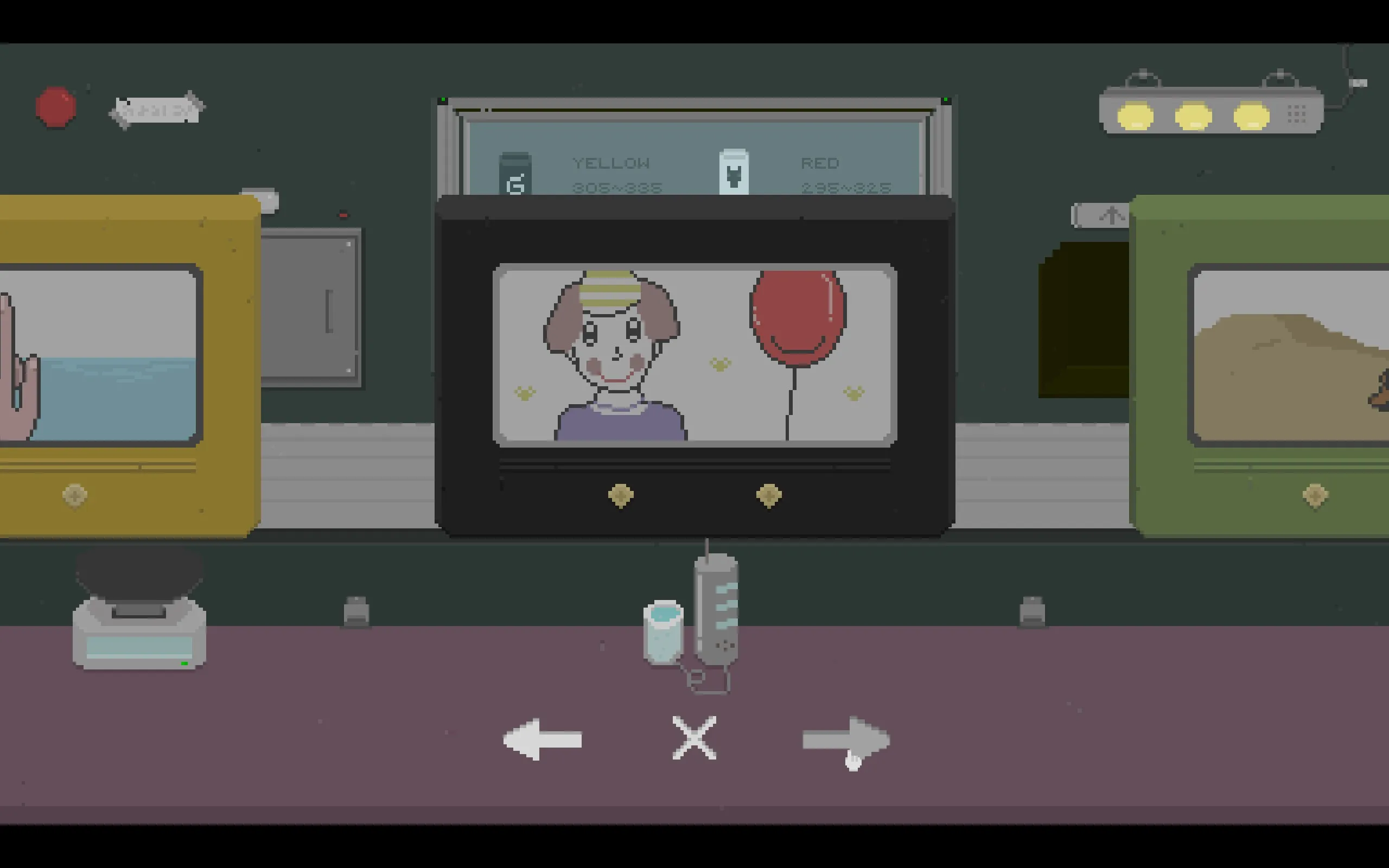

Gameplay moves in two phases, alternating between Ned’s day job of sorting food and ensuring its safety, and the visual novel element of the game. Both elements are familiar to anyone who has played the genre. The job sim aspect involves the player being given a set of criteria to meet, objects to check, and a light time challenge to add a bit of pressure to the work. While I’m not going to claim to be good at this section - having to move quickly while playing on touchpad and staring blearily at pixel art is never my strong suit - there is a satisfaction to the game loop that feels well-earned.

Similarly, while the visual novel element may not be the most compelling story I’ve encountered - especially with its forced romance subplot - it does a perfectly decent job of offering the player moral dilemmas and the sense that their choices are, in some way, shaping the story. While the nature of the game as a dystopian job sim makes the ultimate ending feel inevitable, the particular route to get to that doom felt earned and self-inflicted in the way that a dystopian ending should. That the game forgot some of my choices and occasionally seemed to rewrite its own lore was, on the whole, fine - it got to its end destination regardless, and the path it took to get there was a reasonable one.

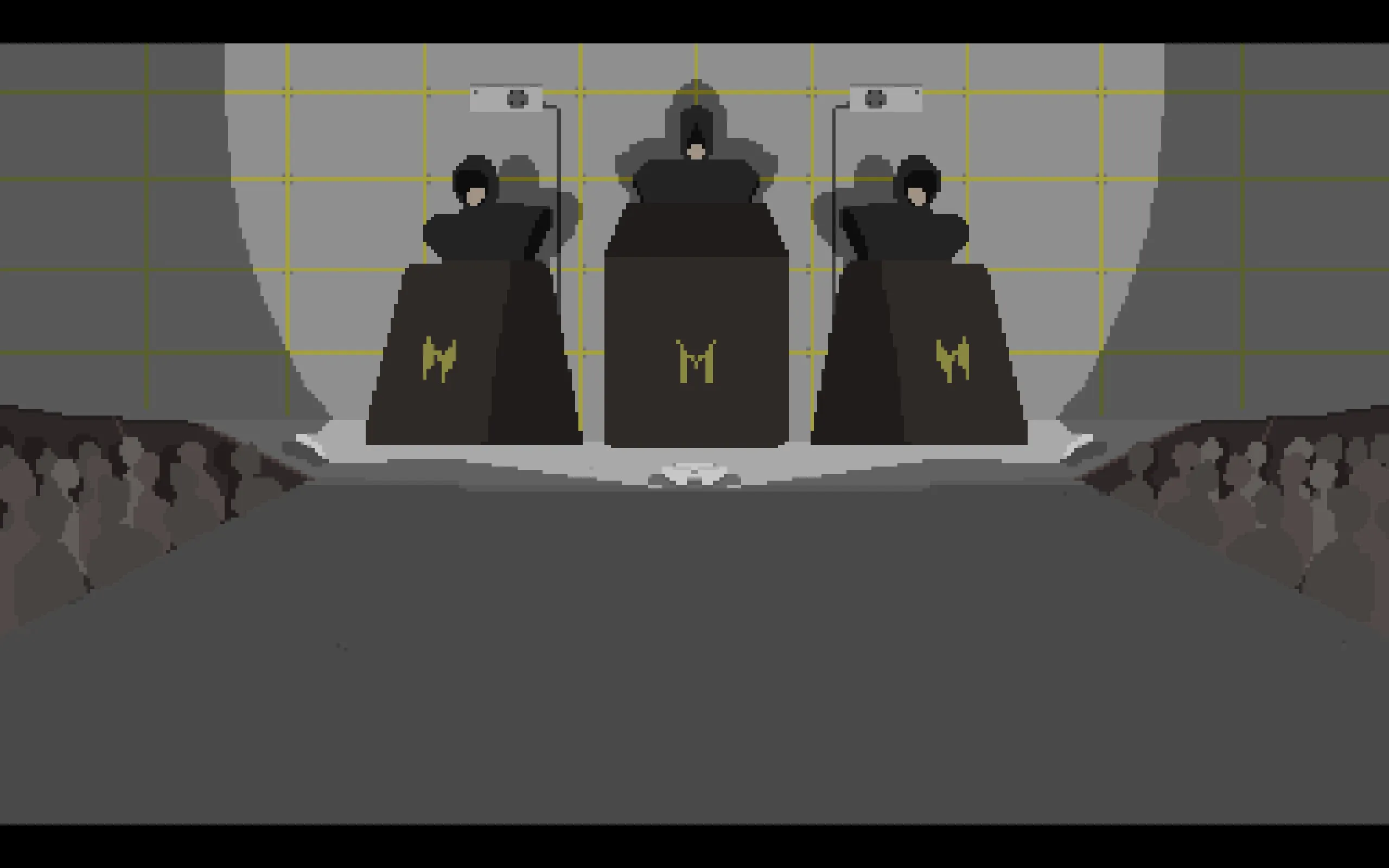

As I sat through the much too long ending, though, my various crimes and transgressions laid out before me, I was left with a question. As I watched this dystopian society decide my fate for stealing food, I was left with the question of why. Why was it that Ned wanted to escape? Why was it that any of this was happening? What made this a dystopia in the first place, and was it, in fact, justified?

No place with happy clown music can be evil

No place with happy clown music can be evil

The obvious answer is that yes, of course Iden is a dystopia. As explained from the game’s first moment, this is a state with tight food controls, immediate and vicious suppression of dissent, and a policy of disallowing any and all emigration or immigration. It is an autocracy, and the type of autocracy that would be right at home in 1984 or the world of Papers, Please.

At the same time, as Ned meets characters from outside Iden, the state of the world as a whole becomes more clear. Iden is not comparable to North Korea, some pariah state isolated but otherwise abnormal compared to the world around it. Iden is, to its surrounding neighbours, a utopia in its well-organised society and relative plentitude of food. At multiple points, Ned meets characters who have smuggled themselves across the border to live in Iden because of the opportunities and relative freedom it presents. This is a crapsack world, and wherever it is Ned is trying to go, that place does not exist. All there is is dystopia and the question of what to do with it.

As with all games in this genre, Ned is offered a choice of either helping a resistance movement or turning them in to the government. When that moment came in Booth, I listened to the resistance movement’s pitch. I heard them out, then decided to ignore them. Whatever they thought they were offering me seemed worse than the reality I already had. In a crapsack world, full of food shortages and work shortages and a world suffering the consequences of climate change, I was fed. I was clothed. I was employed. I was happy. What incentive did my Ned have to leave, let alone upend a system that so richly rewarded him for frankly sloppy work?

And sure, I was thrown before a court in the end anyway, but for the society in which Ned committed his crimes, they were valid crimes and he was correctly found guilty. As far as depictions of dystopias go, while Booth presents a compelling dystopia, it doesn’t present a compelling reason for the protagonist to overthrow that dystopia. This is the greenest pasture, so why not graze in it?

Pro play: Choose Arstotzka

Pro play: Choose Arstotzka

My partner and I have an ongoing disagreement about the meaning of the song “A Gathering Storm” from the musical Hadestown. In the song, Eurydice, disappointed that Orpheus is unwilling to tear himself away from the song long enough to help her take care of the household, leaves him, choosing instead to sell her soul to Hades in exchange for the guarantee of food and shelter (spoilers for a decade-old musical, by the way). The musical doesn’t comment on whether Eurydice’s decision is justified, but instead focuses the story on Orpheus and his journey to get her back from Hades, much like in the original Greek myth on which the musical is based.

Our disagreement is about whether Orpheus is a hero or whether he was a bad partner for neglecting Eurydice in the first place. He chose to set aside the world to focus on his art, leaving her to struggle and fail to provide for them both. On the other hand, it’s never clear what it is she wants from him, whether they have enough, and she wants more. Is it that, though funds are tight, they’re fine, and she just wants more? Or are they genuinely starving, with her having no choice for the sake of her own survival?

Throughout playing Booth, I was reminded of this debate. When Ned sells his soul, what is it all for? Is it because he’s starving, or because he wants something beyond what he can have? We can all dream of being able to be self-actualised while facing the crushing reality that all of us will die in mediocrity and be forgotten within a generation, but what is the cost of striving towards that dream? If Ned is secure, is it foolish to strive for a self-actualisation that, by the very nature of the world, is unachievable? At what point is he selling his soul for no reason?

Ned helps build the wall, my children, my children, and I’m stuck wondering if maybe, Iden doesn’t have a point.

Throughout 2025, my news and social media feeds have been flooded with images of the authoritarian transformation of the United States. Despite - or perhaps because of - the horrors inherent to being a deportation officer, thousands of people have signed up to becomes cogs in the machine of fascism. People choose to participate in inflicting trauma on vulnerable people, choose to make the world a worse place to be, choose to do these things, not out of desperation or because they’re forced into it, but because they’d like to have a slightly better life. They choose to be fascists - and, to be clear, they are fascists - because being a fascist is made out to be a valid thing to want to be. It is not. It never is.

There comes a point in these sorts of job sim games where the player is confronted with a human choice. In Papers, Please, it’s immigrants looking to cross the border because they have no other choice. In Beholder, there’s a variety of characters, trying to survive, and knowing the only way they can do so is to act outside the law. In Booth, there comes a point where the character is faced with a woman on their doorstep, recently snuck across the border from a worse place, and trying to find a place to hide until she can continue her journey. The player has the option to report her, and as I stared at that button, I thought long and hard about all the people applying to become ICE agents.

There’s a risk with all these games of over-humanising the fascist, of taking someone who commits casual evil and making their perspective seem like a reasonable one. Papers, Please and Beholder both strike this balance well, showing a person who, despite not having a choice about their position, nonetheless has the option to do their best within it, recognising their role as a cog, but a cog lacking agency. For games like Booth and Beholder: Conductor, however, that balance is less clear. Ned has the option to turn in Katja, but for what? The reward he would get is to be better able to fulfil his wanderlust, to try his luck at some other place before realising the systems that broke his home broke that other place too.

In Booth, you have the option to roleplay as an ICE agent, and while there is potential value in experience, there is just as much value in leaving voluntary fascists dehumanised.

I chose not to. I understand Ned. I understand why he makes the choices he does. I will not choose to make him into a fascist for his own convenience. I instead choose to leave the fascists faceless and step away from that chance to humanise them.

Developer: Guanpeng Chen

Genre: Job sim, visual novel

Year: 2020

Country: Japan

Language: English

Time to Complete: 6-7 hours

Playthrough: https://youtu.be/RcG2spYJ-j4